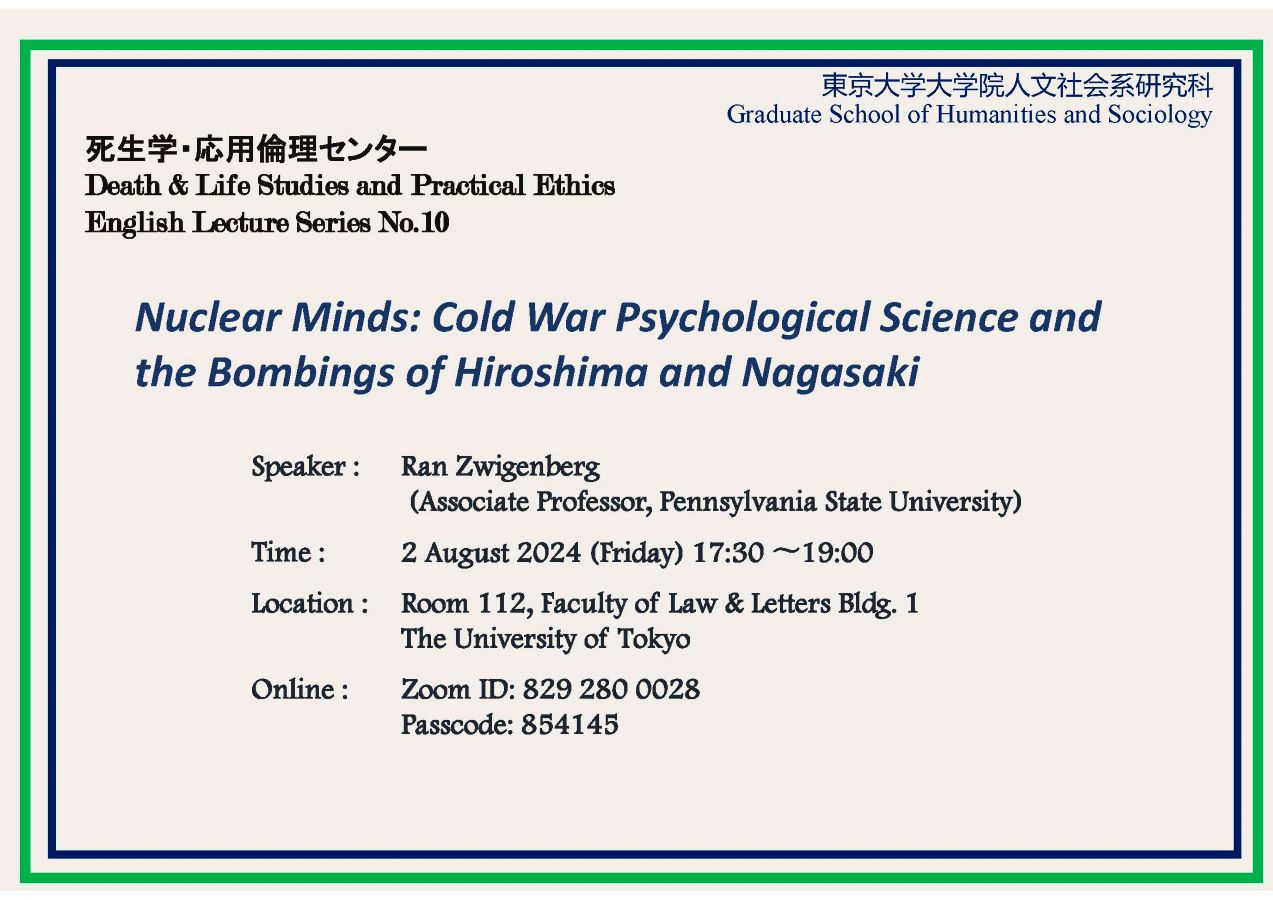

Death & Life Studies and Practical Ethics Lecture Series

Number 010

Ran Zwigenberg, "Nuclear Minds: Cold War Psychological Science and the Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki"

【日時】2024年8月2日(金)17:30-19:00

【会場】 東京大学本郷キャンパス 文学部法文1号112教室

【オンライン会場】Zoom ID: 829 280 0028

【参加について】参加無料・事前予約不要

【使用言語】英語(通訳なし)

【主催】東京大学大学院人文社会系研究科 死生学応用倫理研究室

【共催】東京大学大学院人文社会系研究科

【助成】布施学術基金

※この講演会は布施学術基金により助成を受けています。

Speaker: Ran Zwigenberg (Associate Professor, Pennsylvania State University)

Abstract

In 1945, researchers on a mission to Hiroshima with the United States Strategic Bombing Survey canvassed survivors of the nuclear attack. This marked the beginning of global efforts—by psychiatrists, psychologists, and other social scientists—to tackle the complex ways human minds were affected by the advent of the nuclear age. Nuclear Minds traces these efforts and the ways they were interpreted differently across communities of researchers and victims. The manuscript explores how the bomb’s psychological impact on survivors was understood before the invention/ discovery of the concept of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). In fact, I argue, psychological and psychiatric research on Hiroshima and Nagasaki rarely referred to trauma or similar categories. Instead, institutional, and political constraints—most notably the psychological sciences’ entanglement with Cold War science—led researchers to concentrate on short-term damage and somatic reactions or even led, in some cases, the denial of victims’ suffering. As a result, very few doctors tried to ameliorate suffering. This does not mean the professions “failed” to diagnose PTSD (a non-existent category at the time), rather both doctors and, even more importantly, survivors, understood and experienced psychological suffering and their role in society differently. This is made clear by comparing and connecting the nuclear case with that of Holocaust, military veterans, and other victims. Thus, the book set out, first, to understand the historical, cultural, and scientific constraints in which researchers and victims were acting and, second, to explore the way suffering was understood in different cultural contexts before PTSD was a category of analysis.